Just as European authorities look set to take a friendlier approach to certain kinds of securitization, providing some much-needed relief, the industry faces a new challenge: negative interest rates.

Interest rates on funds held in the collection accounts of securitization trusts are already hovering at or just below zero, eroding the amount of money available to make payments to bondholders.

But there’s an even more unsettling prospect: a negative yield on both the assets held in securitization trusts and the liabilities that these trusts issue.

Could trusts be forced to pay for the privilege of holding the mortgages, auto loans and other consumer loans collateralizing their notes? And could investors in these notes be forced to pay securitization trusts for the privilege of holding them?

While some people think the answer is surely “no,” others aren’t taking any chances. Several new deals contain provisions putting a floor on interest rates.

Key rates in Europe have fallen below zero thanks to the epic quantitative easing undertaken by the European Central Bank and negative base rates set by central banks in Switzerland and Sweden.

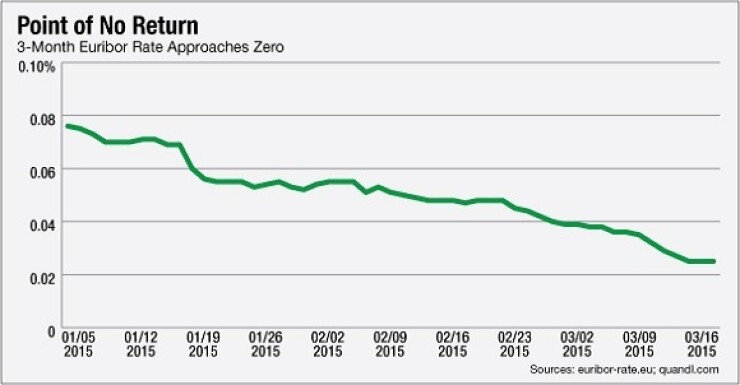

Most European asset-backed securities pay floating interest rates that are pegged to three-month Euribor. So far this benchmark has remained above zero, but it is perilously close to negative territory, at 0.025% as of press time, down from 0.076% at the beginning of the year (see chart below).

The less-often used benchmark of one-month Euribor has already fallen below zero; it is currently at negative 0.011%. One-month Euribor first dipped into negative territory on Jan. 19, then struggled to stay positive through much of February before falling below zero again on the 26th.

A negative benchmark rate doesn’t immediately translate into a negative yield on an asset-backed, since most of these securities all pay the benchmark rate plus something. But if benchmark rates fall far enough below zero, the yield spread on asset-backeds may not be wide enough to leave the absolute interest rate above zero.

Which begs the question, "What happens next?"

The emphatic answer from some quarters is “nothing.”

“What we’ve heard from market participants [is that] the interest paid on the notes would likely always be positive or zero,” said Sebastian Schranz, an analyst at Moody’s Investors Service, who co-authored a report on the issue. He noted that “[a securitization] is drafted as an obligation of the issuer to pay interest to the noteholders,” and not the reverse.

A negative yield on asset-backed securities would imply that noteholders would have to pay the issuing vehicle, whose very “existence” has been established for the benefit of the noteholders, Moody’s stated in its report. This would also lead to a strange pretzeling of cash flows as the funds a trust receives from noteholders would ultimately be returned to those same investors at some point in the future, either when benchmark rates move back up above zero or the deal is refinanced or wound down.

Not everyone agrees, however.

In a January report, BofA Merrill Lynch analysts entertained the possibility that some structured finance bonds could follow sovereign bonds into negative yield territory. The bank noted that some transactions retained as collateral for funding from the European Central Bank pay no premium over their benchmarks and so would follow them into negative territory.

But Moody’s report raises an additional obstacle to this eventuality: a negative yield on issued notes might affect ECB eligibility.

The possibility of paying a special purpose vehicle for the privilege of holding an asset-backed isn’t the only danger posed by negative interest rates. The phenomenon can also eat into excess spread — the difference between the yield on the underlying collateral and the yield paid to investors — as well as eat into the cash in accounts within the SPV.

While most European securitizations pay a floating rate of interest, they tend to be backed by fixed-rate collateral. So it’s common to use fixed-to-floating swaps to ensure that the yield on the collateral moves in sync with bond payments. In the event of a negative benchmark, the floating leg of the swap could potentially turn negative, whittling down the excess spread if the floating payment to noteholders can’t correspondingly fall below zero.

In a January report, Barclays analysts pointed out that in most outstanding deals there are no provisions for a scenario in which the reference rate falls below zero.

But more recent deals are taking this into account, according to market sources. Among them, the 100 million STORM 2015-1, launched this month by Obvion and backed by Dutch residential mortgages; and the 750 million Driver 13, backed by Volkswagen-originated loans, which was completed in January.

“In order to remain hedged in a negative interest-rate environment, the documentation would need to be accompanied by an explicit floor of zero on the floating leg of the swap,” Schranz said.

The collection accounts within an SPV also spell trouble.

Moody’s points out in its report that many deals are already losing money on their these accounts, which tend to pay an interest rate that references a benchmark such as Euribor or Libor minus a spread that is typically 10 basis points to 20 basis points. The negative carry has yet to cause serious issues, but it is certainly another weight on the credit enhancement of transactions in Europe.